FEBRUARY

14, 2016 ![]()

READ

THIS, HUSSY! HE'S MY VALENTINE

Japanese women could be so jealous. Obviously — and I’m not kidding — the title of this print is “Woman Throwing a Snowball at a Girl Reading a Love Letter.”

The 18th-century color woodblock print, by artist Suzuki Harunobu, is part of the collection of the Allen Memorial Art Museum. That's located at my alma mater, Oberlin College. (Motto: On the Forbes list of America's Top Colleges, we’re #46!)

FEBRUARY

13, 2026

![]() RAISING THE FUNDS

RAISING THE FUNDS

My family has been associated with the Methodist Church since at least as far back as 1837, when my great-great-grandfather Dr. Archibald Thomas, a member in Springfield, Tennessee, sold a lot on which to erect a building for his local church.

Some 120 years later in Richwood, Ohio, my father, who had previously solicited donations door-to-door, explained to the congregation how $80,000 for a new Sunday school wing was going to be obtained via voluntary contributions. The script for his talk is this month's 100 Moons article.

FEBRUARY

10, 2016 ![]() CAN'T

STOP NOW

CAN'T

STOP NOW

“Why don’t all drivers out there stop at stop signs?” asked Keith Whitmore of Duquesne, PA, yesterday in a letter to the editor. “I am tired of coming up to an intersection and having a jerk come up to the same intersection and blow through a stop sign. Just by the grace of God I see these drivers first and avoid them before they hit me. ...My dad used to say, ‘He must be late for his own funeral!’”

Personally, I haven’t noticed many cars failing to at least come to a “rolling stop.” And almost everyone seems to stop at a red light and wait obediently for it to change, even with no other traffic in sight. (Why do red lights command more respect than red signs?)

On the other hand, my uncle Jim didn’t even slow down for a stop sign if he deemed it unnecessary. If he could clearly see there were no other cars within half a mile of a rural crossroad, he’d fly through it doing 70.

|

|

FEBRUARY

9, 2026 ![]() COULD SPRING BE NEAR?

COULD SPRING BE NEAR?

The overall warming climate has changed what we're used to. “People have forgotten just how cold it was in the 20th century,” Texas A&M University climate scientist Andrew Dessler tells the Associated Press. For the U.S. in the 21st century, compared to 1976-2000, Climate Central says the average year has had four fewer days of subfreezing temperatures. And consecutive spells of subfreezing temperatures haven't lasted as long.

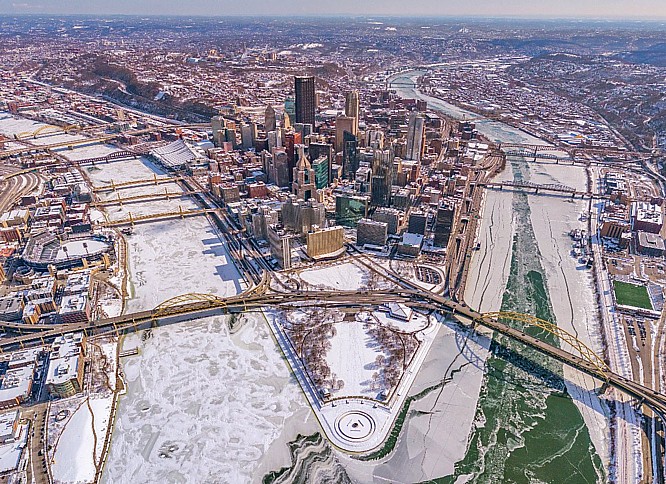

Until this year, that is. In Pittsburgh, we're about to emerge from the 5th longest subfreezing streak in local history. After 18 consecutive days below 32°, the thermometer is predicted to reach 52° here tomorrow!

|

Because of the cold ... and because of more than a foot of snow encasing my car and many roads ... and because of frightening scenes like this Dave DiCello photo of ice-choked rivers ... I have cocooned inside my apartment for the equivalent of two full weeks. That's January 23 through February 2 plus February 6 through 9, a total of 14 days without going outside. During the three relatively survivable days in the middle, I made it to the pharmacy, the grocery, and the doctor before the wind chill returned to -16°. |

|

Ice killed a local citizen Friday morning. Not ICE, but frozen precipitation on Interstate 79 that caused a fatal 25-vehicle pileup. A Slippery Rock University freshman died when he crashed his Subaru into a pickup towing a trailer. At least 20 other vehicles were disabled.

But now it's almost time to break out of this prison!

|

FEBRUARY

7, 2026

Pretentious

writer: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

FEBRUARY

4, 2016 When my father was drafted during World War II, he was first sent to basic training. But the Army realized that this middle-aged office manager was not cut out to be an infantryman. He belonged behind a desk, not on a battlefield. Therefore, they sent him to basic accountant training. I’ve added three pictures to the early part of this article. |

He served overseas but never saw combat. During the year when his age was 35, he was stationed at a base at Chabua in northeastern India and carried the ID card shown above. He was not tall, so he kept his actual height “private.”

By the time he was 36, the war was over, and he sailed home with thousands of his buddies on what could be called a Mediterranean cruise. I’m planning a new picture article about that experience for next month.

FEBRUARY

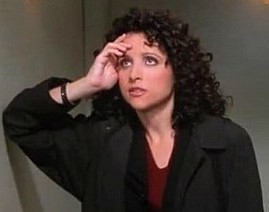

1, 2026 ![]() JULIA LOUIE THREE-FOOT

JULIA LOUIE THREE-FOOT

“Well, Hello Dolly,” Louie Armstrong sang in 1964. “This is Lewis, Dolly.”

|

We're of two minds about how to pronounce “Louis.” A few years ago I encountered a online debate about how to pronounce the middle name of Julia Louis-Dreyfus, the actress who played Elaine on Seinfeld. An internet search led to both correct and incorrect answers. The right one turns out to be the French version, “Louie.” (Julia's prosperous family comes from Alsace, a region that's not quite French and not quite German. And, just for the record, she's more than 16 years old.) |

|

But nobody seemed to be arguing about the “Dreyfus” part. How does one say “Drey?”

• The vowel looks like it could be a long A, as in “they” or “prey.”

• But could it be a long E, as in “tree” or “ski?”

•

Neither, surprisingly. Iit turns out to be a long I

as in “dry” or the German 1-2-3, “eins-zwei-drei.”

(And “fuss” is German for “foot.”)

|

|

Of course, we already knew all that because of the historic Dreyfus affair. Julia's fifth cousin four times removed, Alfred Dreyfus, was a Jewish officer in the French army. In 1894 he was wrongfully convicted of being a German spy, based on what turned out to be a forged document concerning military secrets. The French press and its anti-Semitic faction were convinced of the supposed disloyalty of French Jews, so they welcomed his imprisonment. But in 1898 the novelist Émile Zola wrote an open letter under the headline “J'Accuse...!” How could we forget? |

"I accuse Lt. Col. du Paty de Clam [an amateur graphologist] of being the diabolical creator of this miscarriage of justice and of defending this sorry deed, over the last three years, by all manner of bizarre and evil machinations. ...I accuse General de Boisdeffre of complicity in the same crime, no doubt out of religious prejudice ...I said it before and I repeat it now: when truth is buried underground, it grows and it builds up so much force that, the day it explodes, it blasts everything with it. We shall see whether we have been setting ourselves up for the most resounding of disasters, yet to come."

JANUARY

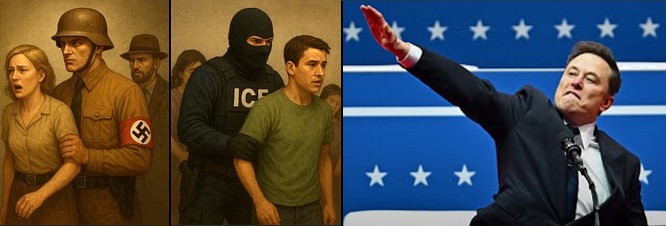

29, 2026 ![]() IMMIGRATION AND DEMOLITION

IMMIGRATION AND DEMOLITION

|

|

Some comments on Bluesky: “A felon who married an immigrant is telling a lot of y'all that the problems in this country all stem from felons and immigrants.” “It's pretty wild that the most rabidly anti-immigrant administration in recent memory is comprised of a President married to an immigrant, a VP married to the daughter of immigrants, an assistant AG in charge of Civil Rights who's an immigrant (Dhillon), and it was all funded by an immigrant (Musk).” |

I am not from the Trump administration. However, like the native Americans whose ancestors crossed the Bering Strait Land Bridge thousands of years ago, I too am descended from foreigners.

|

Not lately, though. My most recent immigrant ancestor was my great-great-grandfather George Scholl. As a teenager, he arrived in the United States from Germany with his parents and three younger siblings in 1846. That was 180 years ago, and the rest of my family tree has an even longer American heritage. |

|

|

Turning now to the Administration's modus operandi exitii, its “method of operating by destruction,” here's our correspondent in Washington. |

|

Hi ho! Kermit The Frog here, reporting from what's left of the White House. You can see the big hole where a huge ballroom is supposed to be built. A law does enable the executive branch to conduct maintenance on the building without congressional authorization. But we frogs are asking, is this maintenance? |

|

According to David Graham of The Atlantic, in a federal court hearing last week Judge Richard Leon remarked that “the law was not intended to cover $400 million projects.” “The hearing suggests the real possibility that Trump will be unable to construct anything in the East Wing's place.”

“Destruction followed by stagnation seems to be something of an MO.” Graham cites the Greenland threats which have resulted in “a tentative deal that appears to closely resemble the existing arrangement, but not before creating bad blood. ...Similarly, DOGE found it relatively easy to destroy USAID, but the administration hasn't been able to create any new way of extending soft power around the globe. ...Trump no longer talks about fully repealing the Affordable Care Act; he and Republicans have now adopted a strategy of slowly bleeding the program. ...Meanwhile, Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy Jr. seems to be having much more luck undermining existing institutions than remaking the nation's public health practices in his idiosyncratic image.”

“Some Democrats have said that any new president who replaces Trump should move promptly to tear down his ballroom. If the project never moves forward, though, they'll have no need. Perhaps they could instead leave the empty site, a fitting monument to the Trump presidency.”

JANUARY

28, 2016 ![]() FIFTY

YEARS AGO TODAY

FIFTY

YEARS AGO TODAY

You’re looking above at a classic 1959 Chevrolet El Camino driving down North Franklin Street in Richwood, Ohio, exactly 50 years ago. It was sunny that morning but very cold. After a low of -2°, by eleven o’clock the thermometer had made it up to zero. As you can see below, the Corn Crib popcorn stand outside Livingston’s store was not open for business.

Local insurance agent John Cheney had decided to take his business to a warmer clime. On his last day in the office, he photographed the scene from his window, all the way up and down the block. That panorama has made it onto this website, and you can find it here.

|

JANUARY

26, 2026 While snowed in yesterday morning with sub-zero wind chills, having little else to do, I read the Columns on page A6 of a Pittsburgh-area newspaper. |

|

JANUARY

25, 2016 ![]() HAVE

WE THE WILL?

HAVE

WE THE WILL?

I’ve been revisiting some old speeches. For example, when President George H.W. Bush took office, he said in his 1989 inaugural address:

|

|

We have work to do. There are the homeless, lost and roaming. There are the children who have nothing, no love, no normalcy. There are those who cannot free themselves of enslavement to whatever addiction — drugs, welfare, the demoralization that rules the slums. There is crime to be conquered, the rough crime of the streets. There are young women to be helped who are about to become mothers of children they can't care for and might not love. ...[But] our funds are low. We have a deficit to bring down. We have more will than wallet. |

As I listened to that last line 27 years ago, I immediately objected. No, Mr. President, it’s the other way around! We have more wallet than will!

Don’t pretend that “we the people” are no longer able to keep our Constitutional promise “to promote the general welfare.” America is the richest nation in the world. Our wallet is bulging. What we lack is the will to open it.

Dr. Martin Luther King, after his return from receiving the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize in Scandanavia, reported: “In both Norway and Sweden, whose economies are literally dwarfed by the size of our affluence and the extent of our technology, they have no unemployment and no slums. There, men, women and children have long enjoyed free medical care and quality education. This contrast to the limited, halting steps taken by our rich nation deeply troubled me.”

Concerned about the U.S. government deficit? Increase revenue. Those of us who can afford it ought to give back more to the commonwealth.

The corporate lobbyists have convinced the fearful and angry among us to contribute tax money for armaments and never-ending wars, but many tightfisted Americans have no inclination to contribute tax money to improve their fellow citizens’ lives.

“The question is whether America will do it,” Dr. King said in Washington four days before his death. “There is nothing new about poverty. What is new is that we now have the techniques and the resources to get rid of poverty. The real question is whether we have the will.”

JANUARY

23, 2016 ![]() PACKERS

vs CHIEFS

PACKERS

vs CHIEFS

I watched Super Bowl I on television for the first time last night. In 1967 I must have listened to this historic game on the radio in my college dorm room. (I'm sure I listened to Super Bowl III that way in 1969. Back then, I myself occasionally announced small-college football and basketball, doing play-by-play on the campus radio station.)

It was the first-ever showdown between the champions of the National Football League, broadcast by CBS, and the American Football League, broadcast by NBC. The game was televised by both networks, but tapes are not available. Therefore, NFL Films has dug film footage out of its vaults and matched it to an edited version of Jim Simpson’s NBC Radio broadcast to produce something resembling a complete telecast. It’s only 90 minutes long because the dead time between plays is not included. NFL Network aired it last night with a minimum of modern-day commentary. Some thoughts from me:

|

|

Kansas City rookie Mike Garrett runs the ball on several nice plays. We would meet in 1989 when I drove the Heisman Trophy winner back from South Bend to O'Hare following a USC telecast. Green Bay’s Jim Taylor, fighting for extra yardage, is thrown to the ground after the whistle by Kansas City’s Buck Buchanan. A 21st-century player would instantly take offense at this lack of respect and his teammates would start a fight, but Taylor does not even turn around. He gets up and walks back to his huddle, leaving it to an official to get in Buchanan’s face and tell him off. The Packers carry a 28-10 lead into the fourth quarter, and the announcers seem surprised that starting quarterback Bart Starr is still in the game. He leads Green Bay to another touchdown, after which both teams switch to their backup QBs. Such substitutions are uncommon nowadays. To me, the officials occasionally appear frenetic, leaping over fallen players at the end of a play to mark the ball as quickly as possible. We could have used energetic officials like that on some of our high school telecasts last season. “Stats! Is it going to be third-and-five or third-and-four?” “I don’t know; they’re still discussing things and wandering around with the ball, and they haven’t marked it yet.” Another good thing about the 1967 officiating: fewer penalties and no challenges. Also, it’s much easier to sit through a fast-paced 90 minutes of action than a complete live telecast that’s more than twice as long. |

|

JANUARY

22, 2026 It was announced this morning that Norwegian actress Inga Ibsdotter Lilleaas has received an Academy Award nomination for her supporting role in Sentimental Value. But what sort of name is Ibsdotter? I gather that it's Scandavian for “Ib's daughter,” just as Henrik Ibsen's name means “Ib's son” and Gunnbjörn Ulfsson, the first European to sight Greenland, was “Ulf's son.” And who is “Ib”? A diminutive of Jacob, or a type of wood. |

|

JANUARY

21, 2026 ![]() FIRST MONTH OF THE SEVENTIES

FIRST MONTH OF THE SEVENTIES

Neither in college nor in graduate school did I have a TV set in my room. Thus I missed a lot of television during those five years. In particular, I did not see either of the broadcasts that Mark Evanier describes in this article. But I was there, almost. I was actually in Johnny Carson's studio a week later.

The first of Mark's two programs appeared under the title of The Kraft Music Hall on January 21, 1970.

|

I recall the previous decade when the Kraft title was applied to a variety show starring singer Perry Como. Announcer Ed Herlihy, a veteran of movie-theater newsreels, voiced apparently live commercials featuring closeups of cheesy dishes. But this particular Music Hall had no music. It was billed as a Friar's Club “roast” of Jack Benny. |

|

|

|

The first playful jokes were taped separately and delivered by the Vice President of the United States, Spiro Agnew, seen here. This was only two months after his opinions of broadcast news and its unfairness to the Nixon administration had been discussed at Syracuse University, where I was a member of “Sequence 22” working toward a master's degree in radio and television. The actual roastmaster for this program would be Johnny Carson. |

The Benny roast aired on a Wednesday during the first week of semester finals at Syracuse. As graduate students, we had no exams scheduled for the second week. Therefore we took the opportunity, sometime around January 26, to take a chartered bus to New York City for three days of talks by people in the broadcasting industry down there. Included was a behind-the-scenes tour of the NBC facilities at 30 Rockefeller Center, including Johnny Carson's studio. (His Tonight Show would move to Burbank a couple of years later.) Click here for my recollections.

JANUARY

19, 2026 ![]() MIDWINTER MADNESS

MIDWINTER MADNESS

In our nation's first century, ballot counting and interstate travel required considerable time. Therefore four months were allowed between Election Day and the date when the winners were sworn in.

But once technology had improved, the 20th Amendment to the Constitution (ratified in 1933) eliminated six weeks of unnecessary lame-duck waiting. The Inauguration of the President was rescheduled from the relatively-mild March 4 to the always-frigid January 20.

|

I always thought that was a bad idea. Late January is the coldest part of the year in this region. For example, look at tomorrow's prediction. Thirty-two years ago today, on January 19, 1994, temperatures in Pittsburgh began with a low of -22 and climbed only to -3 that afternoon. Fortunately, over in Washington, D.C., there was no outdoor ceremony scheduled for the steps of the Capitol the next day. |

|

|

“Now, it's bigger than I told you. After realizing we're going to do the Inauguration in that building, it's got all bulletproof glass. It's got all drone, they call it drone-free roof. Drones won't touch it. It's a big ... it's a big, beautiful, safe building.” |

But there was a ceremony planned for January 20 in 1985. when the noon temperature would be 7° above. On that occasion (left) and again in 2025, the swearing-in had to be moved indoors. President Donald Trump promises that the weather won't be a problem in the future. Why not? Three weeks ago at a press conference, after claiming that Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell's renovation of the central bank's headquarters would cost “up to $4.1 billion,” he compared that to his own pet project. “I'm doing a magnificent, big, beautiful ballroom that the country has wanted — the White House has wanted for 150 years. It's a massive job, and it's a tiny fraction of that number. And we're under budget and ahead of schedule.”

|

Nevertheless, it won't accommodate “a million and a half people,” which is what Mr. Trump thought the shivering audience on the Mall looked like at his first Inauguration in 2017. The high that day was 48°.

JANUARY

18, 2016 ![]() REMAINING

AWAKE

REMAINING

AWAKE

Last night the American Heroes Channel ran a documentary on the 1968 hunt for Martin Luther King’s assassin. They called it Justice for MLK.

Perhaps they should have called it Revenge for MLK. James Earl Ray’s pursuers were not seeking justice as much as retribution.

For Rev. King, “justice” was not the electric chair. It was equal rights, and “we will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.” Justice was not about punishing bad people. It was about guaranteeing good people the opportunities they deserve.

|

|

I never met Rev. King, although as I related in this letter, I met his father at a photo op in Marion, Ohio, in 1970. The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. did visit my college several times, but that was before I arrived as a freshman in the fall of 1965. Dr. King’s final speech on campus had been delivered that spring. For easier reading, I’ve condensed the text of that commencement address, “Remaining Awake Through a Great Revolution.” In observance of MLK Day, I’ve posted it here under the title To Dream, But Not to Sleep. |

|

|

|

JANUARY

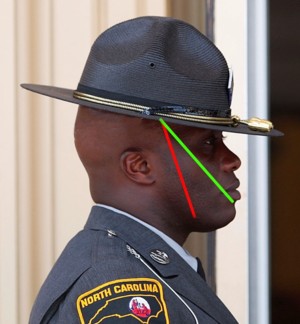

16, 2026 Some 150 years ago, shortly after Canada became its own dominion separate from Great Britain, its North West Mounted Police began wearing an element of the British Army uniform: red coats. A quarter of a century later, they replaced their helmets with broad-brimmed “campaign hats” like those worn by Canadian cavalry during the Second Boer War. |

|

These hats often included a strap to keep them on the Mountie's head. The strap was attached to the inner edge of the brim, midway between the front and back. Thus the strap could be run either across the front of the skull or across the back. Nowadays in the US, the uniforms of many state troopers and highway patrol officers include similar hats. The headgear is worn with a forward tilt to express no-nonsense seriousness. |

|

|

|

However, various parts of the country have front-vs-back disagreement Some states keep the strap at the back of the head, where I think it belongs. |

|

|

|

Others try to emulate the front-mounted chin straps on football helmets. But there's a problem: even with the campaign hat tilted forward, its strap is typically too short to fit underneath the chin (red line). The alternative is to slide it into the little gap between the chin and the lower lip (green line). |

|

To me and many others, these lip straps appear ridiculous, as in this frame from a January 13 newscast. They look like they'd get into the trooper's mouth and affect his ability to speak and give orders. The straps seem to be threatening to slide up even higher and become nose straps, like the luggage that ensnared Jim Carrey in the movie Liar Liar. Pennsylvania and other states need to correct their uniform regulations! Even the President knows the headgear's strap goes in the back.

|

|

JANUARY

13, 2026 ![]() AS IT WAS 83 YEARS AGO TODAY

AS IT WAS 83 YEARS AGO TODAY

Terrible things are happening outside.

Poor helpless people

are being dragged out of their homes.

Families are torn apart;

men, women and children are separated.

Children come home from school

to find that their parents have disappeared.

Everyone is scared.— Diary of Anne Frank, January 13, 1943

One or two thousand additional federal agents are being deployed to Minneapolis as part of the Trump administration's latest effort to crack down on immigration. JD Vance says he thinks the deportation numbers will go up once they get more agents hired and going door to door.

Retired Ambassador Ken Fairfax: A reminder from Huffington Post that DHS and ICE have opened fire on unarmed civilians 16 times since Trump took office, killing 4 people. In every case, DHS claims that the victims “assaulted officers” and/or tried to ram them with cars. In every case, evidence proves they are lying. Every time.

Charlotte Clymer: He didn't shoot her in the head at point blank range because he felt like he was in danger. He shot her in the head at point blank range because he was furious that she wasn't afraid of him. He felt emasculated.

David French: The shooting in Minnesota is exceptional only because Good died, not because the administration lied. In fact, for the Trump administration, lying is the norm. Trump isn't a responsible leader, and he's at his absolute worst in a crisis. He lies. He inflames his base. To the worst parts of MAGA, your worth is defined by your obedience. And those who don't obey? Well, they deserve to die, and no one should mourn their death.

Michael Squires: If law enforcement needs a mask to conduct their daily duties, that should tell you all you need to know.

David French: And — most dangerous of all — the administration pits the federal government against states and cities, treating them not as partners in constitutional governance but as hostile inferiors that must be brought to heel.

Scott Centoni: They don't have to cancel elections. They plan to send ICE to swarm election sites in cities in swing states. Shoot a few nearby immigrants here, arrest a few citizens there, it doesn't take a lot of boots on the ground to depress turnout by 20%.

JANUARY

12, 2016 ![]()

DIGEST

VERSION: NOVELTY'S WORN OFF

Under the new four-team college football playoff format, the second annual national championship game last night (Alabama 45, Clemson 40) drew noticeably less interest than last year's much-ballyhooed first game. At least around here it did. Pittsburghers care about only Steelers football. Clemson plays in the same conference as the University of Pittsburgh, but that means nothing. Yesterday’s advance story about the upcoming college championship was buried on Page C-5 of the sports section.

|

I got an offer in the mail yesterday to re-subscribe to Reader’s Digest. Apparently, the little monthly still exists. Way back in 1958, when I was 11 years old, my family took a summer vacation trip that led ultimately to a rustic inn on Rangeley Lake in Maine. I felt rather like the compulsive reader “Brick” from The Middle, because there wasn’t room to take any of my books. There might be no television, and local newspapers would be rather sketchy. I might be reduced to reading cereal boxes. Therefore I slipped into my suitcase the latest edition of Reader’s Digest. Like this copy, it contained one condensed book and 30 articles “of lasting interest” gleaned from various magazines. I rationed myself to read exactly three articles each evening. |

|

|

JANUARY

10, 2026

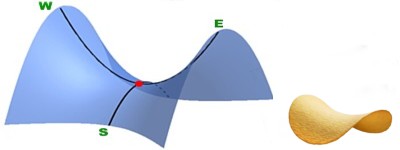

The theoretical blue hill is saddle-shaped. If you drive across it from west to east, the red dot seems to be the low point. But if you're driving from south to north, the red dot seems to be the high point. |

|

In my new apartment at noon on Saturday, April 14, 1974, I realized that such hyperbolic paraboloids are shaped like Pringles, the stackable “potato chip” from Procter & Gamble which may have been named for a suburban street north of the company's Cincinnati headquarters.

I had to share my discovery with my old college friend. The letter I wrote is part of this month's 100 Moons article.

|

It goes on to describe little computers I owned in the Seventies, plus a larger one I bought at the start of the Eighties. |

JANUARY

9, 2016 ![]() YOURS

IS ONLY MILD-TO-MODERATE

YOURS

IS ONLY MILD-TO-MODERATE

Commercials often feature actors portraying real people speaking directly to us. “My rash was really bothering me. So finally I went to the doctor.”

However, I’ve seen a pharmaceutical ad that begins, “My Moderate-to-Severe Chronic Plaque Psoriasis made a simple trip to the grocery store anything but simple. So finally I had an important conversation with my dermatologist.”

Do you ever speak with such clinical specificity? I think I’d like to have an important conversation with Humira’s ad writer.

|

|

That’s because I myself suffer from Moderate-to-Severe Chronic Advertising Copy Incredulity. For example, on a rack of tanks outside a store, I saw this slogan: “It’s not just propane.” So of course I had to wonder. “It’s not just propane? What else do they put in that tank? Rocket fuel?” |

|

|

Then he told me, “Check out this here literature. Blue Rhino is ’specially careful with their propane tanks and propane accessories. That’s your ‘what else!’ “Every tank is cleaned, or even repainted. Then it’s labeled with all your safety information and instructions. They test it for leaks, fill it up with just the right amount of propane, and deliver it to the store. |

“Of course, they don’t deliver to Mega Lo Mart no more. Not after the big blowup over there.”

|

2026 UPDATE: On TV commercials and print offers, we often see fine print at the bottom to keep the lawyers happy. And radio commercials sometimes end with gibberish: a voice speeded up so much to fit the time allotted that one can't understand it. Lately I've heard an alternative in which the announcer notes that "teas and seas" are available online. There's no explanation of teas and seas. I suspect they're initials for Terms and Conditions, but who can tell? |

|

|

JANUARY

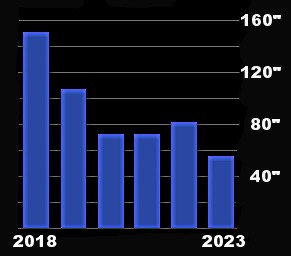

7, 2026 Introducing Bob Costas recently, Peter Sagal referred to Bob's alma mater as “the Harvard of broadcasting skills.” Naturally, that would be the Newhouse School at Syracuse University. I also attended that “Harvard.” Some of my Master's degree classmates from Newhouse have been reuniting occasionally via Zoom. Last fall the current Dean, Mark Lodato, was our guest. He informed us that Syracuse, New York, still does get cold in the winter, but there's a lot less snow than we had to slog through in 1970. Was he right? Of course some years bring more snow than others, but Syracuse is in the lake-effect belt downstream from the Great Lakes. Below are recent annual snowfall totals. |

|

|

|

The chart implies that the climate has indeed been changing, especially since 2018. Nevertheless, Almanac.com says that the city still averages 114.3 inches of snow per year. And last year they had 121.6 inches — more than ten feet, making Syracuse once again the snowiest major city in the United States. They've been the snowiest spot in New York State for 39 of the last 73 years. (Buffalo is second with only seven wins.) And what about this winter? More than two feet fell at Syracuse Hancock International Airport on December 30, the second-snowiest day in the city's recorded history! As of January 2, 2026, the city had already recorded 79.2 inches of snow, over double its normal total for that date. More is to come.

|

|

|

JANUARY

5, 2026 ![]() TODAY'S THEME: W-OR-D CHOICE

TODAY'S THEME: W-OR-D CHOICE

As a one-time physics major, I learned (I hope I've got this right) that quantum mechanics describes very tiny particles as “wave functions” of probabilities. The particle may have a 33% chance of being over here but also a 33% chance of being over there, so we might say it's “in” both places at the same time. Theoretical physicist Erwin Schrödinger admitted that this concept seems absurd if we try to apply it to large objects, such as a cat in a sealed box. According to quantum rules, the cat is in a “superposition” of being both alive and dead simultaneously! That is, until we open the box and the act of observation forces it into one state.

As a part-time puzzle solver, I'm amazed at the ability of crossword creators to find words with particular qualities to fit their bizarre themes. Of course, there are some 600,000 words in the Oxford English Dictionary, so they do have choices to sort through.

A standard 15-character-wide New York Times Monday puzzle referenced a rare basketball achievement with the entry QUADRUPLEDOUBLE and then somehow came up with three 15-character examples: aCCeSShoLLywOOd, miSSmiSSiSSiPPi, and weLLwhOOpdEEdOO.

One constructor, Sam Ezersky, said that to build a Sunday puzzle “it took months to cobble together" this set of ten before-and-after pairs: pensive ex, managed micro, complete auto, heated super, penultimate ante, African pan, solving dis, apocalyptic post, standard sub, and vision pro.

The Times crossword for Thursday, October 9, 2024, caught my eye in particular. It was the third by constructor Grant Boroughs to appear there, and his first Schrödinger puzzle (named after the superposed cat). In the Times crossword column “Wordplay,” Deb Amlen explains that in a Schrödinger puzzle, “certain squares accept more than one letter, and using either letter is considered correct. That means a Schrödinger puzzle accepts both versions of a changeable entry, even though there is only a single clue.”

Boroughs had to find a dozen entry pairs with the following properties: The two words or phrases can each be referenced, maybe obliquely, by the same clue. (That rules out pairs that have little in common, like WORM and DORM.) The two words or phrases are identical except for one letter which I'll call the “cat.” I'll depict it with the symbol Ø to mean, in this case, “either W or D.” And in each pair, the “cat” is either the first or last letter.

|

Here are the dozen pairs he came up with. In his grid he chose two of the pairs to cross at the “cat.” For example, |

|

|

|

COØ |

Major

food source animal |

The resulting creation, says Ms. Amlen, might just put Mr. Boroughs on the map of constructors to keep an eye on.

JANUARY

3, 2026 ![]() RESPOND WITHIN TEN MINUTES!

RESPOND WITHIN TEN MINUTES!

Some fundraisers like to set an arbitrary goal and an arbitrary target date, then challenge donors to reach that goal before the deadline. I received several such requests last month, many noting the practicality of hurrying up and making a charitable contribution while the 2025 tax deduction still was available.

Others may have received the late-December pitch below, headlined “Uh oh... Troubles are BOILING OVER.” The post mentioned three Presidential deadlines.

|

|

It threatened workers with losing their promised $2,000 to illegal aliens if they didn't respond in the next hour. It warned of a “very likely” loss of Congress if another goal wasn't reached by midnight tomorrow. And it predicted a Communist takeover of the Democrat[ic] Party if yet another goal wasn't met in less than 48 hours.

Only

the second Trouble is at all likely. But after these deadlines

pass, MAGA won't bother you again — until 2026.

|

|

Fundraisers never mention that it doesn't really matter whether or not their artificial goal is met. They'll gladly accept your promise of a “$58 monthly seed" or other cash even if you don't get it to them until after the target date. They're merely trying to frighten you into immediate action before you have time to think about it. |

|

|

|

Canadian comedian Norm Macdonald, currently appearing as KFC’s Colonel Sanders, sometimes posts lengthy items on Twitter by breaking them up into individual sentences. This week he used more than a dozen tweets to transmit a piece he appears to have written 42 years before. On December 20, 1973, Norm was growing up in Ottawa. TV news reported the tragic deaths that day of Admiral Luis Carrero Blanco (terrorist bomb in Spain) and singer Bobby Darin (open-heart surgery). Also, 10-year-old Norm couldn’t stop thinking about two men who perished earlier in an attack on an airplane. He was sure his own death was coming soon, somehow. On December 30, here’s what he must have written. I’ve edited the schoolboy spelling and punctuation. |

I’m scared, because I asked dad about a thing on TV I saw. Some hijackers threw a live man and a dead man off a plane. My dad gets mad and says TV isn't for 10-year-olds. I get more scared now, because I can see him scared. It happened some days ago but is still shown.

Then one day last week I heard my dad say a prime minister in Spain was killed and “that ain’t no coincidence.”

My mother is crying. My mother says nothing’s good no more, and even Bobby Darin's dead and he was better than Sinatra. Dad says “the kid knew he was a goner.”

I couldn't sleep good for a while, but the world didn't go, and Christmas wasn't ruined.

And then today, a man with the scariest name of Carlos the Jackal tries to kill somebody.

I know I won't grow to be old. Sometimes I wonder if I'll make it to 11, but most days I think I will — unless a weird thing happens. But I don't for a second think I'll be 12.

You see, I've been watching what’s really happening in this world on the TV when dad's gone. And when I tell my mom what’s happening, she cries. And she holds me and tells me everything is all right. But if everything is all right, why is she holding me and crying?

I whisper in her ear. I tell her it gets darker every day, and can't she see it? She pushes me away and goes to where the bottles and glasses are.

And then my mother’s brother barges in, and I know real fear, more fear than Carlos the Jackal. I run to my room before he sees me. I turn off the lights. I am all under the covers.

My mother won't let anything happen. I hear her sing “Mack the Knife” real hard, and I hear my uncle's hard voice tell her to shut up and give him a glass, but she sings louder.

I am finally found by sleep.

This felt familiar. I too went through a period of pre-adolescent angst. Fortunately, in my case, what frightened me was merely the global situation, not a drunk uncle. In my case, my father didn’t tell me to stop watching the news, but my mother did tell me we shouldn’t worry about things over which we have no control. I recalled the experience in this post-9/11 article.

Angst is “a feeling of deep anxiety or dread, typically an unfocused one about the human condition or the state of the world in general.” We fear horrible things are about to happen. What things they may be, we cannot tell.

But demagogues and other politicians are quite willing to gain our support by scaring us even more, making us even more afraid. The government is coming to take our guns! The Mexicans are coming to rape our women and take our jobs! The environmentalists will take our SUVs! The Muslims will behead us!

Such overblown trepidations are no longer merely ludicrous, writes Scott Renshaw from Utah. “I can't laugh at scary, delusional, desperately-frightened-of-change people any more. There are too many of them, causing too much damage.”

“Who wouldn’t be depressed about the world today?” asks another Canadian, Margaret Wente, in a Christmas Day article in The Globe and Mail. “Everywhere you look, it’s doom and gloom. So, turn off the news and consider this. For most of humanity, life is improving at an accelerated rate!

“Most people find this hard to believe. After all, we’re programmed to look for trouble. Here are some reasons to start the new year on an optimistic note:

“This year, for the first time on record, the percentage of the world’s population living in extreme poverty has sunk below 10 per cent, the World Bank says. This is a stunning achievement. As recently as 1990, 37 per cent of the world’s population was desperately poor. ...Malnutrition has all but disappeared, except in countries with terrible governments. Eighty per cent of the world’s population use contraceptives and have two-child families. Eighty per cent vaccinate their children. Eighty per cent have electricity in their homes. Ninety per cent of the world’s girls go to school.”

What about violence? “We’ve never lived in such peaceful times,” says Wente. “Wars and conflict fill the news, but they are at historic lows. ...As for terrorist attacks, you’re far more likely to be killed by a collision with a deer. ...Between 1993 and 2013, according to a Pew Research Center analysis, the rate of U.S. gun homicides fell by half, from seven homicides for every 100,000 people to 3.8 homicides in 2013.”

What about illness? “We are gradually wiping out the worst of the world’s diseases. In 1988, polio was endemic in 125 countries. Now, there are just two: Afghanistan and Pakistan.”

“Make a New Year’s resolution,” Wente advises, “to count your many blessings — including flush toilets, electric lights, polio vaccines, and peace.”

As the apostle Paul advises in the fourth chapter of Philippians, 6 Do not be anxious about anything.

His recommendation goes something like this: 8b If there is anything excellent, if there is anything worthy of praise, think about those things instead. 7 And the peace of God, which surpasses all understanding, will guard your hearts and your minds.

EARLIER

POSTS BY MONTH:

|

2025 |

||||||||||||

|

2024 |

||||||||||||

|

2023 |

||||||||||||

|

2022 |

||||||||||||

|

2021 |

||||||||||||

|

2020 |

||||||||||||

|

2019 |

||||||||||||

|

2018 |

||||||||||||

|

2017 |