The

Vanderbilt Cup

Written July 2021

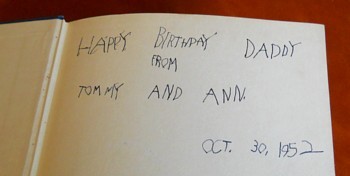

It was the fall of 1952. I was a precocious kindergarten student. My father, soon to turn 43 years old, was about to become a small-town Chevrolet dealer.

|

And my mother found an automobile-related birthday present for him. She told me how to inscribe the flyleaf of our gift.

|

|

|

|

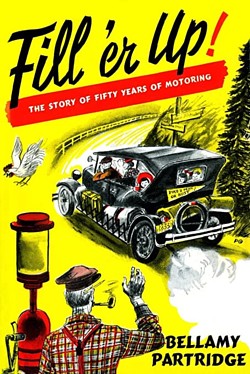

The book was Bellamy Partridge's “story of fifty years of motoring” — partly history and partly the author's personal recollections of his adventures. One of them was a 1905 jaunt from New York City to Buffalo at the age of 28 in a used two-cylinder Rambler. Seven years later, he and his wife and another couple spent two months driving all the way to California over the proposed route of the future Lincoln Highway, later to be designated US 30. But it was I, not my father, who spent the most time poring over the volume. It's still in my bookcase. |

|

Fill 'er Up! recalls early milestones, like the first auto show and the Glidden Tour. It describes in great detail the first American automobile race, from Chicago to Evanston and back on the snowy Thanksgiving Day of 1895. The Duryea brothers' motor wagon (right) won at an average speed of 7 mph. |

|

In the next decade, a much faster auto race was established, the Vanderbilt Cup. Bellamy Partridge tells about it in his eleventh chapter. For this website, I've gathered some illustrations from the Internet and imagined a conversation with the author, in which he speaks with excerpts from his book.

|

|

Welcome, Mr. Partridge! Let's turn the calendar back to the beginning of the 20th century — to the year 1904 in particular. |

|

|

Most of the people in America thought the motorcar industry was booming. Was it? |

||

It was, and still there were those among our traveled folk who were greatly concerned because our automotive development was so far behind that of Europe.

|

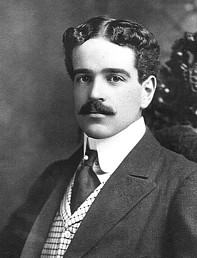

This worried Mr. William K. Vanderbilt, Jr., who firmly believed that racing was the best proving ground on which the manufacturers could test the quality and merit of their product. I'm told that “Willie K.” was a wealthy playboy whose great-grandfather, Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt, had owned the New York Central Railroad. He had loved cars ever since the age of 10, when during a stay in the south of France he rode 4½ miles to Monte Carlo in a steam-powered tricycle. That was in 1888. |

|

Back in New York, at the age of 20 he imported a French motorcar. He acquired more, and soon he was speeding through Long Island towns on his way to his parents' summer estate.

He had driven in a number of European road contests in the days when a racing driver could wear a derby hat in a road race without exciting comment or having his hat blown away by his speed. But he was, in fact, strictly an amateur and was often spoken of as a gentleman racer.

The morning of January 27, 1904, found 26-year-old Willie at Daytona, piloting a 90-horsepower Mercedes over the Florida sands of Ormond Beach.

|

|

He covered a flying mile in only 39 seconds. His speed of 92.3 miles an hour was a world record! “Really, I did surprise myself,” he remarked. Later that year he brought European-style road racing to his home state. |

|

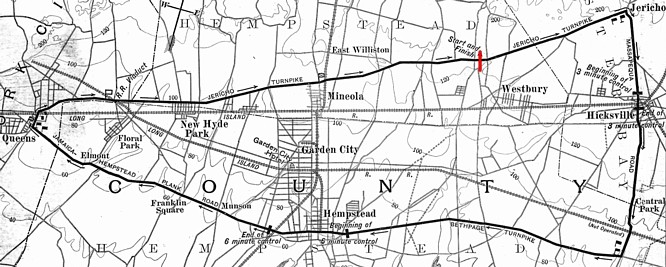

A 30-mile circuit was mapped out. It made use of public roads, from the eastern edge of Queens halfway to Idle Hour, his parents' estate out on Long Island. |

|

|

His grand prix would be known as the Vanderbilt Cup. The cup was a stupendous trophy nearly one yard in height. He established the race under the sanction and sponsorship of the American Automobile Association (AAA). Some three months in advance of the event he and his sponsors had posted along the course a notice which read as follows: |

|

An automobile race over a distance of between 250 and 300 miles will be held for the William K. Vanderbilt, Jr. cup on Saturday, October 8. The start will be at Westbury at daylight.

All persons are warned against using the roads between the hours of 5 A.M. and 3 P.M. Officers will be stationed along the road to prevent accidents.

The Board of Supervisors of Nassau County has set aside the following roads for the use of the racers on October 8.

Jericho Turnpike, from Queens to Jericho;

Massapequa Road, Jericho to Plain Edge;

Bethpage Road, Plain Edge to Hempstead;

Fulton Street, Hempstead to Jamaica.

A reduced rate of speed will be maintained while passing through Hicksville. Three minutes will be allowed to pass through the village. Six minutes will be allowed to pass through Hempstead.

|

I'm told that the procedure worked this way: At a control, a driver was required to slow and stop between two tapes stretched across the roadway 25 feet apart. The car was inspected and its arrival time was recorded and handed to an escort on a bicycle. Then the car and its escort were allowed to proceed to the end of the control, located just beyond the railroad crossing. At Hempstead, this was 1.4 miles away, so the average speed was a sedate 14 miles per hour. |

|

|

|

After six minutes (or more if a train had interrupted the driver's progress), the car was allowed to resume racing. The entrance and exit times were reported to the officials' grandstand by telephone, and the elapsed time was deducted from the car's total race time.

All persons are cautioned against allowing domestic animals or fowl to be at large. Children unattended should be kept off the roads. Chain your dog and lock up your fowl. To avoid danger don't crowd into the road.

This announcement must have generated cries of protest from the local residents. I understand you have a clipping from the distinguished New York Times.

“The farmers of Nassau County are asking what the common roads are for. To notify those who need to use the roads to keep off them on a certain day, that the owners of road locomotives may run at dangerous speed, is calculated to start an inquiry.”

Only four days before the race the Times carried another story in which it described the “embattled” farmers.

“They announce their intention of carrying firearms to protect themselves in case their lives should be menaced by the precipitate scorchers.”

But after a public meeting and a ruling from the county judge, the race went on.

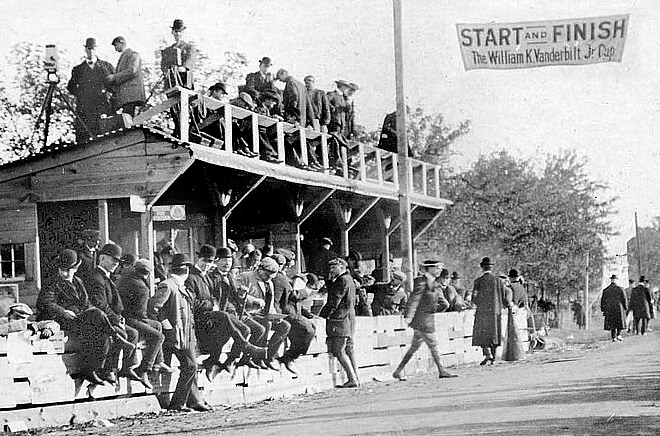

Precautions had been taken to make the course as safe as possible for both spectators and contestants. The dirt roads had been scraped and oiled, and the AAA Racing Committee had erected at Westbury near the start and finish line a grandstand seating 400.

Opposite

the grandstand was the judges' stand, shown below. On the

upper left, notice the cameramen setting up their tripods on the

roof, just like television crews today. Here

is some Biograph motion-picture footage from this camera location and

others around the circuit.

What

kind of vehicles were entered?

Six from France with some of the most famous cars and skillful drivers; four from Germany; two 90-horsepower Fiats from Italy with daring and colorful pilots. Five American cars came through the elimination trials, three of them White Steamers which failed at the last to be ready for the start.

Every car would carry a "mechanician" in addition to the driver. One of his jobs would be to watch out for overtaking vehicles, as the rear-view mirror had not yet been invented.

Back in the city, there must have been much excitement.

More than 50 breakfast parties had been scheduled at the Waldorf-Astoria for the day of the race, which was to start at six o'clock in the morning.

|

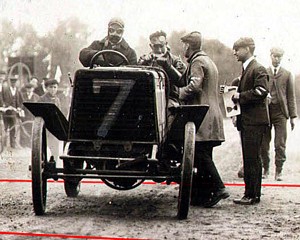

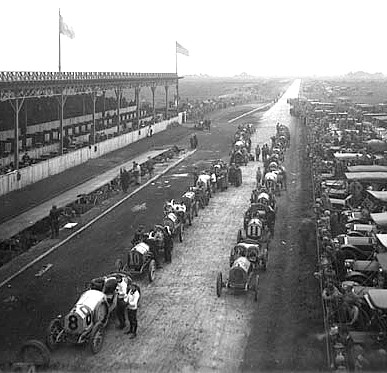

At the start/finish line, I'm told that starter Fred Wagner lined up the odd-numbered cars on one side of the course and even-numbered cars on the other. However, unlike today's races, everyone didn't take off in a bunch when the green flag dropped. I presume that was to avoid crashes at the first turn. |

|

|

|

|

|

Car #1 was sent off promptly at 6:00, car #16 fifteen minutes later, and so on. The results would be based on elapsed time, so the first car to cross the finish line would not necessarily be the winner. |

|

The breakfasters would have to be on their way soon after midnight if they were to reach the grandstand in time for the start, for it was quite obvious that the dirt roads leading out on the Island would be choked with the vehicles of spectators going out for the race.

|

|

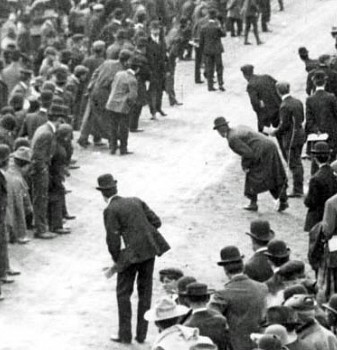

Thousands of people did not get within walking distance of the course until the race was nearly over; for instead of lasting until three o'clock, as planned, the race had to be called soon after midday because of the unruly conduct and riotous behavior of the great crowd of spectators numbering some 25,000 who came swarming out on the course, endangering not only their own life and limb but that of the race drivers as well. |

|

So who won? George Heath, an American resident of Paris, driving a 90-horsepower Panhard carrying the colors of France, closely followed by Albert Clement also of the French team. Heath had driven a fine race over a difficult course, making the 284.4 miles in five hours and 26 minutes at an average speed of 52.7 miles per hour. Five cars, three of them American and two German, were running when Clement crossed the line. But when the word went out that the race had been called, the crowd did not even wait for the racers on the track to get back to the starting point, but hustled into their cars and started for home regardless of the racers who might come crashing into them at 70 miles an hour — and in no time at all the entire course was jammed with homeward-bound traffic. |

|

Was anybody seriously hurt?

Only one fatal accident: Carl Menzel, mechanic for the Mercedes driven by George Arents, was crushed under the car and killed when Arents lost control while making a turn at high speed.

What was the public reaction to this event? I understand that a writer named E.P. Ingersoll had opposed the idea from the beginning.

He scoffed at the waste of money used in building the great racing monsters described as a danger on the course and useless anywhere else; and he vilified road racing as tending to foster the speed craze which he branded as the bane of automobiling. For Horseless Age he wrote a stinging editorial in which he called the contest “the bloodiest event of the kind since the ill-fated Paris-Madrid race of a year and a half ago.”

But others must have found value in the competition.

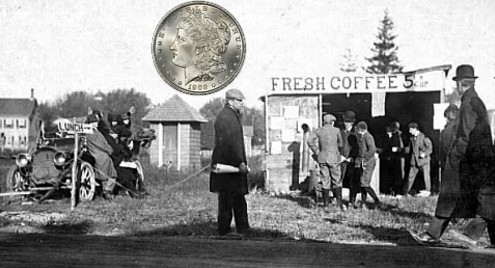

The mechanical-minded saw weaknesses in cars that should be corrected. The people of the Island saw something quite different. It was round, it had an eagle on one side and a portrait of the Goddess of Liberty on the other. The official name for it was the Almighty Dollar.

They had found that spectators would pay almost any price for a good parking place and as much as $25 for the use of a bed overnight. (It was a time of low prices. Men's fine shoes cost $5.) Sandwiches and apples were in great demand, and even toilet accommodations could be charged for.

|

|

So popular demand led to a second race the following year. Were there any changes? The course had been considerably revised. |

It did need to be shorter, especially since a 30-mile lap took 30 minutes to complete and only five cars were running when the 1904 race was called (left). A spectator would watch a competitor roar past, and then it might be many minutes before the next one came along.

|

~ |

1904 |

1909 |

Typical nowadays |

|

|

~ |

Vanderbilt |

Vanderbilt |

Le Mans |

Formula 1 |

|

Length of a lap |

30.3 miles |

12.6 miles |

8.5 miles |

3.2 miles |

|

Number of cars |

5 |

16 |

62 |

20 |

|

Average separation |

6.1 miles |

0.8 miles |

241 yards |

282 yards |

|

Wait between cars |

6 minutes |

45 seconds |

4 seconds |

4 seconds |

In general, early motor racing's lengthy courses did become shorter over time. For example, there's the Italian Grand Prix.

|

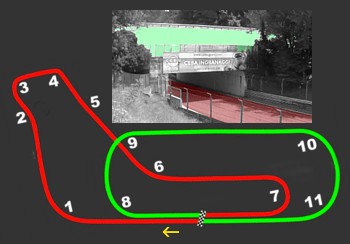

|

The custom-built Autodromo Nazionale Monza opened in 1922 with a length of 6.2 miles or exactly ten kilometers. For compactness, it consisted of two superimposed circuits: a road course depicted here in red, and an oval in green. |

The road course began with a Curva Grande (Big Bend), and later (inset) it ducked under the 21° banking of the oval's #9 Curva Alta Velocita (High-Speed Turn). The two portions shared the wide main straightaway, where on every lap drivers would have to cross over from one side to the other. Nowadays Formula 1 racing no longer uses Monza's oval, only the 3.6-mile road course.

Sorry for the digression, Mr. Partridge. You were about to describe the 1905 Vanderbilt. I'll bet the crowd was even bigger than the first year.

The Long Island Rail Road put on special trains leaving for the Vanderbilt Cup course at three and four o'clock in the morning.

|

|

A large party of Bridgeport folk, enthusiastic over the Locomobile racer built in their town, chartered the steamer Isabel to take them to Oyster Bay so that they might approach the course by the back door, thus avoiding all traffic from the metropolitan area. It would have been a success had they possessed the foresight to engage transportation to take them halfway across the Island to the scene of the race. |

|

Which drivers were competing this year? All the best talent of the European racing fraternity was on hand. Most colorful of them all was Vincenzo Lancia, a giant of a man, swaggering and boastful, profane and jovial. He had the throttle down to the floor boards much of the time and drew cheers from the bloodthirsty crowd every time he went roaring past the stand. By the end of the fourth lap he led the field by more than a quarter of an hour. His first 100 miles were clicked off at 72 miles per hour. |

|

However, he decided to stop for new tires at his Fiat station just east of Albertson. A painting by Peter Helck depicts what happened next.

Anxious to be on his way, Lancia started to pull out of the control when his mechanician saw Walter Christie coming down the stretch wide open and thundering like a freight train; he bellowed at Lancia to stop. But Lancia never wavered. He was gunning up his mount to get sufficient momentum for the speedway, and Christie, never dreaming that Lancia would fail to hear the thunder of his exhaust and give him the right of way, made no move to change his course until it was too late. Christie struck the Fiat almost full in the back.

Nowadays Lancia would be penalized for an "unsafe release." The impact smashed his rear wheels, and replacing them set him back an hour. But what about the car that hit him?

The Christie car turned a complete somersault, hurling the mechanician through the air as if he had been shot out of a cannon. The body turned slowly as it went sailing along and landed in a plowed field with no worse injury than a broken rib. The car went end over end and landed a heap of junk.

There must have many been other wrecks. Were the spectators thrilled?

They probably did not hope that anybody would be killed, or terribly maimed or mangled — but if such a terrible thing should happen they did not want to miss it. They wanted to be in a position to see, and they did not hesitate to smash down barriers and fences in order to get into an advantageous if extremely hazardous position.

And some of those positions were right out on the roadway itself.

The crowd was greatest as well as most dense at Albertson's Corners where three telephone poles along a serpentine turn were most promising of smashups and bloodshed. Here the plain-clothes deputies were unable to control the crowds at all. On his fourth round Foxhall Keene slammed into one of the poles, wrecking the car but tossing the occupants into the clear.

|

And Louis Chevrolet, while driving at high speed on Willis Avenue, grazed a pole which deflected him into a fence, a large section of which he carried with him into a field where his axle was broken by striking a projecting boulder. What a mess. |

|

After the race was over, the course looked like a junk yard. Wrecked cars costing thousands of dollars to build were strewn along the road. Discarded tires, castoff oil cans and empty bottles cluttered the right of way along with paper bags, cardboard boxes and other litter from the thousands of picnic lunches eaten on the side of the road

Nevertheless, the event with its spectacle and its speed now had a classy reputation.

The big cup race smacked of the smart set, the Four Hundred, the polo field — and it wore the Vanderbilt trade-mark. The contest had become the most popular and most fashionable of our sporting events. It quickly took a place in public esteem akin to that of the World Series at the present time, only the Vanderbilt had a bluestocking flavor that baseball, being of the people, never could have.

In Part Two of this story, we'll read how an innovative concrete roadway became part of the circuit in 1908. Then in 1910:

“They're three wide coming out of the Metropolitan turn! Now four wide!” And that was just the traffic headed to the race.

“Five fans are huddling under robes in a Packard, waiting for the dawn!” And one of those spectators was our author, Mr. Bellamy Partridge.