|

|

|

Jan |

||||||||||||||

|

^ |

January 1968

Added to website

January 1, 2018

One reason I had chosen Oberlin College was its sobriety. There were no beer blasts and no frivolous “Greek” organizations. We were there to learn.

|

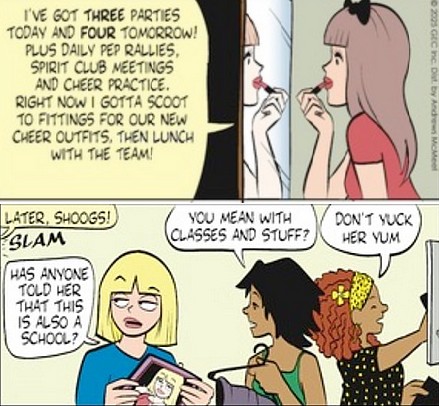

UPDATE: The opposite situation was depicted in “Luann” for August 24, 2025. But in my day Oberlin observed the in loco parentis principle (it looked after us in place of our absent parents), and the family was rather puritanical. |

|

|

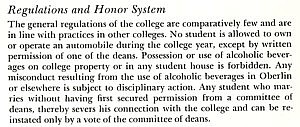

The 1964 introductory booklet “About Oberlin” included the paragraph at the right. It claimed that the college's rules were unremarkable. |

|

Of course students couldn't be permitted to drive, or drink, or marry. That was fine with me. The campus was small enough to walk everywhere, I didn't drink, and I didn't plan to wed. Others might chafe at these requirements. By the time I matriculated, in fact, the rules had been relaxed to allow low-alcohol 3.2% beer. But we were far from being a “party school.” Secret societies, meaning fraternities and sororities that discriminate against the non-elite, had been banned at Oberlin since 1847.

That's a good policy, considering that fraternity hazing nowadays kills about four young Americans every year. About half of these tragedies involve alcohol overdoses. In 2017, 26 members of Penn State's Beta Theta Pi fraternity were charged in the death of a pledge whom they'd forced to down at least 18 drinks in 82 minutes.

However, not every student remained in our monastic paradise for the full four years. One of my classmates transferred after our sophomore year to a bigger school that incidentally did have fraternities — Ohio State. That would be Jack Heller from Warren, Ohio.

With some reservations because Jack was Jewish, for Christmas 1967 I had sent him a card to catch him up on what he was missing.

I told him about the little get-together our Noah Hall housemother, Mrs. Chamberlain, had thrown us before the holiday break. (I was still living in Noah, the same dorm that had been my home as a sophomore. That's my single room on the left below.)

I also mentioned that it had been a while since I'd seen Humphrey, a basset hound who had sometimes visited Jack and me and the rest of our math class. Humphrey wasn't enrolled; he was merely auditing. He'd waddle into the room and sit quietly in the back, except for a very occasional howl if he got bored.

Jack replied on January 4, 1968.

I hope you survived Mrs. Chamberlain's cookies. Is Charlie the Hippie still there — or did he burn down Noah?

I think Humphrey transferred to a new school, probably because the Dean of the College refused to recognize him as a faculty member and four-legged institution. I remember, however, the dog that looks like a fox as it visited my Math 4 class one day. (Now tell me, why do Oberlin pooches go only to math classes? Are these courses really for the dogs?)

In my last letter, I preached about the advantages advantage of OSU (social life). Now for the disadvantages. Actually there's only one glaring fault here, and it's a bad one — the complete lack of an intellectual group or intellectual activities.

Result: You can't win. At Obie, no one has the time to indulge in the many intellectual endeavors. At OSU, where time is abundant, the only indulging is on a liquid level.

Lots of luck on your finals, Tom.

Sincerely,

37090 (brings back memories, doesn't it?)

That's a student ID number. As I recall, Oberlin had required us to identify ourselves as we entered the cafeteria line for lunch each day.

First Things First

I was not yet thinking about final exams. On January 4 we had only just returned to classes, and I was busy overseeing three live sports broadcasts in three nights on our campus radio station.

|

On that Thursday, I rode with the basketball team to Cleveland, where the wind chill was 20 below. I called the play-by-play of Oberlin's game at Adelbert (now part of Case Western Reserve University). On Friday our hockey broadcasters traveled to Bowling Green State University. I remained at the station, editing highlights for our 11:00 news. And on Saturday I went to Columbus for a basketball game against the Capital Crusaders. Unfortunately, technical difficulties forced my partner to “recreate” the broadcast from a nearby office, and our 120-mile return trip in a snowstorm took more than three hours. |

These adventures are detailed here. |

Winter was definitely with us. On the following Saturday, January 13, eighteen inches of lake-effect snow fell on the Oberlin campus.

It was still snowing the next morning, so I skipped my usual routine. On a normal Sunday I'd go to breakfast and church and come back to the dorm to read the Plain Dealer, but with a foot and a half of snow outside, I stayed in my room and worked on a term paper for Physics 35. It was due Wednesday. Having consulted three books from the library, I was now composing something like a textbook chapter.

|

I spent nine straight hours on the project Sunday plus a few more Monday afternoon. The ten-page paper got an A, with the comment of “a very fine, lucid presentation.”

That may be. However, I must confess that I can no longer make heads nor tails of it. I didn't pursue a career in science, and in the last 50 years I've forgotten all I ever knew about Maxwell's equations and PDEs.

I can, however, understand this sentence that I wrote to my parents. “I think I've been enjoying myself at Oberlin more the past two months than ever before. The radio work and the people I know are a lot of fun, and I'm worrying less about my schoolwork — while still working at it just hard enough to get good grades.”

The Game of the Century

The following Saturday night, January 20, there was a much-hyped showdown between two undefeated college basketball teams. Elvin Hayes and the #2 Houston Cougars hosted Lew Alcindor and the #1 UCLA Bruins. It was such a huge event that it was played in the Astrodome before 52,693 fans.

|

This was the first nationwide NCAA regular-season prime time telecast. TVS syndicated the game to at least 120 stations. Here's some video. Apparently only three cameras were used. I don't think there were any TV sets in my dorm, and there may not have been a national radio broadcast. But I did find the game on the radio in my room. I think Cleveland's WEWS was carrying the telecast, and by turning my dial all the way to the left I could tune in Channel 5's audio at 81.75 FM. |

|

One of my neighbors heard it and knocked on my door. If you're watching, may I join you? I had to explain that I was merely listening.

UCLA's regular announcer, the late Dick Enberg, called the play-by-play. Later he said, “That was about as great as it will ever be. ...Big game, big crowd, first time a college game ever televised nationally, and then to have this remarkable, magical performance by Elvin Hayes and Houston winning. ...That was the platform from which college basketball's popularity was sent into the stratosphere!”

As a lowly graphics operator 20 years later, I happened to pass Mr. Enberg in an NBC hallway at the Seoul Olympics, and he actually smiled and said hello. He was indeed, in the words of Sean McManus, “a consummate professional and a true gentleman.”

Programming a Station

On early evenings, between 6:00 and 7:30 PM, most Oberlin students were in their dining halls. They weren't listening to the radio. Therefore WOBC broadcast what some people might consider “filler,” beginning at 5:45 with an easy-listening DJ show called Dinner Date. Station Director John Heckenlively took a shift behind the mic, hosting the Date on Mondays.

Around 7:10, we aired about 20 minutes of recorded public affairs. These once-a-week shows were educational in tone and promotional in purpose — they came to us free of charge — and included such titles as:

Men and Molecules

Scope

Voices

of Vista

Italian Panorama

Patricia

in Paris

Germany Today

Now, as the incoming Program Director, I was auditioning similar programs. For example, at 10:00 on Monday evenings I scheduled a one-hour show from CSDI, the Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions. The first two speakers would be Julian Huxley and Bishop James Pike. Later topics would be “The Negro as an American: Is There a New South?” and “The Bleak Outlook: Jobs and Machines.” (When the season's final episode ran short, I put together some recorded odds and ends I called The Discard Pile, featuring the Armenian Nightingale.)

Saturday evenings at 7:00 we aired a 13-part history of Canada, The Coming of Age, because we could.

Was anyone listening to these public service tapes on our little ten-watt noncommercial FM? We hoped so, but maybe not. Ken Levine has blogged about the paucity of complaints received by his California commercial station after one middle-of-the-night show mysteriously played at hhaallff ssppeeeedd.

We planned other changes in WOBC's program schedule for the second semester. Our directors of classical and popular music were responsible for many of these shows, and they gave them titles like Old Swedish Organs and The Chicken Duck Show. (That first one was actually about historic pipe organs. The other one was hosted, of course, by Chuck and Dick.)

There were only three semester final exams on my schedule — no math final — so I had time to get my studying done in the mornings. Afterwards, you'd find me at the radio station. Between turning in my term paper on Wednesday through the following Monday, January 22, I spent about 25 hours there. Then our nine-day Classical Music Marathon began.

Discovering Hidden Treasures

“Once I get started at WOBC,” I wrote, “I can't seem to stop until the day's over. I must admit I enjoy that stuff more than studying physics. But most of my enjoyment is the novelty of it — the adventure of finding out what's on those mysterious unlabeled reels of tape.”

The non-music reels and records were stored in the Program Cabinet in the outer office. One of them turned out to be a recording of the station's first broadcast on November 5, 1950. Another was Dr. Martin Luther King's October 22, 1964, speech in Finney Chapel, when WOBC's coverage had been piped into Hall Auditorium for an overflow crowd.

|

|

In 2023, members of the Class of 1967 recalled Dr. King's appearances, beginning with "a very ill Martin Luther King addressing the community in Finney Chapel in November 1963. The standing ovation lasted longer than his brief remarks. If the Oberlin City fire marshal had entered the building and seen the occupation of every seat and square foot of floor space, he would have had a heart attack. Civil Rights was the foremost public issue when we entered in September 1963." —Ted Rafael |

|

"I remember standing at Finney for the MLK speech. People had climbed to sit on the window sills. We all left the chapel singing 'We Shall Overcome.' When he came back our senior year, we had to get (free) tickets to see him. They didn't want a crowd like the earlier one." —Gloria Wolvington Hurdle "I remember sitting on the floor in Wilder, waiting for the free tickets to be distributed. I sat for so long near the front of the line that both my legs fell asleep, could barely stay upright to get the tickets. But it was worth it. Like you, my memories of that visit and the first one are almost as vivid as yesterday." —Molly Horst Raphael "His appearances at Finney are among the most notable memories of my life. His aura permeated the entire Chapel and has stayed with me ever since." —Daniel Brent |

|

I also found a cardboard box containing sets of 331/3 rpm records for possible future use, labeled “The Rum Runners & MLK.”

The Rum Runners was a CBC comedy series about the adventures of a revenue man in Canada's Maritime Provinces during the era when liquor was prohibited in the United States. The 13 half-hour episodes were written by Nova Scotian broadcaster Norman Creighton. WOBC never aired it, as far as I know. At least it didn't cost us anything.

“MLK” referred to a collection of Dr. King's speeches and sermons. Ten weeks later, we would have occasion to open that box.

|

COMING IN FEBRUARY: Musicians perform in the studio (including a couple of announcers who would later go on to fame), I partner with another physics major in the lab, and we exchange gifts (including a pesticide record and a whimmydiddle). Click here to continue. |